On the drizzly autumn Friday of November 11th, 1983, US President Ronald Reagan would have no time for his customary Oval Office nap. Besides delivering a speech that morning to the American Legion in honor of Veterans Day, Reagan then filled the rest of his schedule taking part in a NATO nuclear war exercise under the designation Able Archer. The president found the subject matter fascinating but frightening; despite his firebrand speeches, he also hoped the Soviets understood they had nothing to fear from America. His hope was in vain.

In Moscow, General Secretary Yuri Andropov saw Reagan’s role in Able Archer, underscored by America’s recent invasion of Grenada and a worldwide security alert of US forces, as the cover for a nuclear first strike. Escorted early after a freezing sunrise along with chief of the General Staff Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov to the Politburo’s subterranean command bunker by his elite KGB troops, with crushing sadness and dread Andropov transmitted his directive, a desperate attempt to minimize the looming devastation his country faced.

Later that evening, the NATO exercises having concluded, Reagan conferred with National Security Advisor Bud McFarlane, ate dinner, and set out with his wife Nancy for Andrews Air Force Base to begin his long trip to Japan. Marine One happened to pass over a wholly ordinary US Air Force Jeep on the highway below as the chopper made its approach to Andrews. Inside that Jeep were four airmen in the smart blue berets of the Air Force Security Police, the sergeant speaking with a southern Illinois accent, though he had grown up in Khabarovsk. The group had transited the Canadian border a week prior, having been directed to a safe house in a suburb of Washington, DC, to await orders. Their orders were in: under the guise of a Security Police patrol and with the right documents and no questions asked, they managed to enter Andrews, filter through layers of security and conceal a device the size of a large briefcase, to be activated by satellite signal, in some brush opposite the tarmac an hour before the president’s arrival.

Reagan, greeted at Air Force One for a short debriefing on Able Archer by Secretary of Defense Cap Weinberger and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs John Vessey, was looking forward to being the first American president to address Japan’s parliament, the Diet. Yet the day would never come – the pouring rain simply evaporated as a fireball of hellish intensity rose up to incinerate Andrews Air Force Base.

The four airmen in the Jeep, on their way southward into Virginia, witnessed the terrible flash illuminate the night sky behind them. Here and across the Atlantic, other groups, heretofore invisible, were descending like packs of wolves upon their targets. Speaking little amongst themselves while checking their weapons, they raced down I-95 toward their next objective in darkness: the power grid of the whole eastern seaboard had just gone dead.

Such a horrific turn of events was more likely than we would care to consider. Thankfully, Reagan decided not to participate in Able Archer and rather went straight to Japan to address the Diet. Andropov and the Soviet leadership, while on razor’s edge over what they viewed as provocative US-NATO moves, didn’t overreact. Instead of this nightmare scenario coming true, East and West would live to tell of another narrow escape from Armageddon during the dark days of the Cold War. Yet the armed services and spies of both sides would continue to stand at the ready for any eventuality – the following is the true story of the KGB’s special units.

The KGB – Instrument of Soviet Global Power

From the mid-1970s to the 1980s, the Soviet KGB created a fearsome capability for counter-terrorism and special operations, one that made Western strategists nervously re-evaluate their plans and projections. With the potential for conflict with the United States and NATO – from the risk of nuclear exchange to brushfire wars in the Third World – only growing, such dangerous circumstances required the creation of special units distinct from those of the General Staff’s GRU (Glavnoe Razvedyvatel’noe Upravlenie– Main Intelligence Directorate).

As the USSR’s premier secret service, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti – Committee for State Security) carried out intelligence and covert action worldwide. Soviet power was approaching its global zenith during the era of détente, and Lubyanka looked to field a more comprehensive special-forces capability then it had previously. The GRU, after all, was already focused on wiping out key military personnel and facilities of the “main adversary” shortly before war would break out. As chairman of the KGB, Yuri Andropov wanted to craft a similar instrument that the Kremlin could apply to the wider geopolitical spectrum. Andropov and his men were truly innovators in this regard, founding elite special-missions units that provided the Soviet leadership with options for discrete, direct action during crisis conditions with the West.

Alpha: The KGB’s Shield

Andropov first devoted a considerable amount of attention and effort to the formation of new spetsnaz (special purpose) groups because of their value in guarding the Soviet Union from potential blackmail by terrorists, which could produce a corrosive effect on political stability. The Politburo and KGB leadership were particularly concerned by the possibility of hijackings and terrorist acts by nationalist groups that called for independence from Moscow. An Armenian extremist cell, for example, committed three nearly simultaneous bombings in Moscow on the 8th of January 1977 before they were apprehended by the KGB eight months later[i].

To answer the terrorist threat, Andropov decided to institute a brand-new commando force within the KGB. In 1974 Unit “A” was formed under the 7th Directorate (Surveillance), but was subordinated directly to the chairman of the KGB[ii]. The team, now popularly known as “Alpha”, was trained for anti-terrorist functions on Soviet territory. Alpha originally consisted of approximately 30 hand-picked men, but as its utility was recognized, the number of officers, as well as funds and special equipment, increased. Alpha also participated in the interdiction of hostile intelligence operations and the seizure of Western agents (“snatch-and-grabs”) within the Soviet Union[iii].

Alpha, however, was endowed with a strategic purpose apart from just combating terrorist phenomena or snatching spies. Andropov was well aware of the West’s development of elite special operations forces such as Delta, SAS, and GSG-9 and sought a counter to their likely infiltration into the USSR in the event of hostilities. US and NATO special-missions units would be tasked with the assassination of the Party leadership and Soviet high command and the sabotage of strategic objects. Alpha, therefore, was designed to protect the Politburo’s senior members and key facilities during war or periods of heightened tension.

The group’s strategic task is confirmed by another fact relating to the optimization of the KGB’s structure. In the same year of Alpha’s founding, 1974, the 15th Directorate, responsible for servicing the Kremlin leadership’s underground bunkers, was accorded the title of a chief directorate, a significant upgrade in status[iv]. Detachments from both Alpha and the 15th Chief Directorate conducted training exercises escorting Politburo and Central Committee officials into command-and-control nodes buried well below the famous Moscow Metro system. It is reported that Andropov viewed these rehearsals with utmost seriousness, despite his chronic physical ailments, after he assumed the General Secretary’s seat in the early 1980s[v]. By the time of the failure of détente and escalating tensions over US intermediate-range missile deployment in Europe, Andropov had reason to plan out contingencies.

Vympel: The KGB’s Sword

The KGB did not cease the development of special operations forces with Alpha; Andropov sought to create a special-missions unit that could infiltrate hostile territory and execute direct actions, such as assassinating the enemy high command and destroying strategic infrastructure. The First Chief Directorate, responsible for foreign intelligence, maintained within its apparatus the super-secret Directorate S (Illegal intelligence). This was the KGB’s arm responsible for highly covert intelligence work without the refuge of diplomatic status or any association with the Soviet government. Directorate S operations typically involved the penetration of an intelligence officer (often with a spouse) into a country as natives of that land or immigrants from a third country in order to gather intelligence and run agents. Henceforth, the illegals would also facilitate the missions of deep-cover commando teams.

There was certainly an organizational base for Andropov to draw on for his new project, and previous endeavors showed the need for a more systematized, permanent structure for special operations. Earlier a Department V for planning sabotage and assassinations, heir to the infamous 13th Department of the 1950s, had been created within the First Chief Directorate in 1969. Concurrently there was established an Officer Corps Development Course (KUOS) in Balashikha, on the outskirts of Moscow, to prepare a “special reserve” of KGB operatives for crisis and war. Department V was disbanded, though, after one of its officers, Major Oleg Lyalin, had defected to the United Kingdom while there on assignment in 1971[vi].

Clearly the KGB needed a highly secret, cohesive combat unit in a constant state of readiness to be deployed abroad at a moment’s notice to protect Soviet interests. Such an elite commando group would be of inestimable value during a crisis situation or war, for it could potentially succeed in “decapitating” the enemy’s leadership, thereby forcing a more beneficial outcome to a conflict for the Soviet Union. In 1976, five years after Lyalin’s disastrous defection, Foreign Intelligence’s Directorate S, the Illegals, assumed control of KUOS and instituted the 8th Department, henceforth responsible for assassinations and sabotage in foreign countries[vii]. The time was coming when such actions would be ordered by the Politburo.

KGB special groups- the temporarily formed Zenit from the First Chief Directorate and the Grom detachment from the 7th Directorate’s Alpha – did indeed manage the textbook decapitation of a target state[viii]. Yet this operation did not take place in a NATO member state, but rather in crisis-ridden Afghanistan in late December 1979. The action could be seen as a dress-rehearsal, albeit under differing conditions, for the strategic paralysis of NATO governments if the Warsaw Pact were ever to launch its armored divisions into West Germany. The spetsnaz teams accomplished an operational success in assassinating Afghan President Hafizullah Amin at the behest of Leonid Brezhnev’s Politburo, yet the Soviet Union was dragged into a brutal, decade-long morass that was a strategic catastrophe. Nonetheless, the KGB’s special detachments continued to show their operational and tactical effectiveness throughout the Afghan war. Such activities included reconnaissance, intelligence and sabotage operations, as well as killing or seizing leading figures among the CIA-backed mujahedin[ix].

The KGB’s most elite special missions unit, Vympel (Pennant), was finally established in August of 1981 within the 8th Department of Directorate S. Maj. Gen. Yuri Drozdov, a veteran of the Illegals Directorate and its chief from 1979 until the end of the Cold War, characterized Department 8 as “nothing less than an information and research intelligence structure, which followed by operational means everything concerning NATO special forces.” Drozdov says that his illegals even underwent special-forces training in NATO armies[x]. One can only wonder which Western nations unwittingly played host to Soviet deep-cover officers in their most sensitive commando outfits, but such first-hand knowledge would have been put to good use by the KGB in order to fashion Vympel a cut above its competitors.

Known officially as the Separate Training Center, Vympel was tasked with special operations abroad, including sabotage and direct-action missions against hostile states. The officers who composed the unit were selected not only from the KGB, but from all the Soviet armed services, and passed through an extremely rigorous regimen of all-conditions commando training, language instruction, intelligence work, and instruction in driving all manner of vehicles[xi].

Along with combat duty in Afghanistan, officers of the unit undertook “advisory” assignments in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Angola, Mozambique, and other locations of the Cold War’s proxy conflicts throughout the 1980s[xii]. Vympel operators also likely engaged in “force protection” for vital intelligence operations in dangerous conditions in addition to hunting down terrorists threatening Soviet interests. Drozdov tells of Vympel’s 1985 action against a Palestinian group that had kidnapped three Soviet diplomats in Lebanon:

In Lebanon citizens of the USSR were taken hostage. Negotiations with the terrorists weren’t producing any results. And suddenly, one after the other, the bandit leaders began dying under unclear circumstances. Those who were still alive received an ultimatum: if the hostages are not released, then they will have to choose among themselves who will be next. After two and a half months, they released our men[xiii].

The veteran spymaster then mentions an operation in which Vympel operators disembarked from a submarine onto the coastline of a foreign country during a midnight storm, penetrated deep inland, and snatched a person targeted by the KGB for their possession of crucial intelligence. Within hours the team was back on the submarine, along with a new passenger, and on its way to the Soviet Union[xiv].

On the Brink of Doomsday

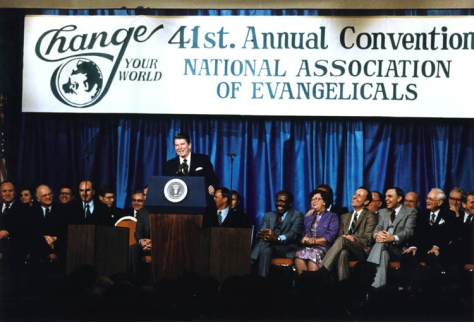

Aside from counter-terror work and high-risk intelligence missions, Alpha and Vympel’s ultimate purpose was to short-circuit World War III, or at least provide the Soviet Union with an opportunity to win it. Andropov ordered the creation of Vympel in particular amidst Kremlin fears over what actions newly-elected US President Ronald Reagan might undertake vis-à-vis the USSR. The Soviet intervention in Afghanistan and the deployment of intermediate-range SS-20s within striking distance of European cities were all within the context of increasing tensions with the West. Along with an arms buildup already ongoing since the late 1970s, under Reagan the US struck an offensive policy course of “containment” and covert warfare. Andropov, soon to be General Secretary, was among the first to realize that the Soviet economic engine was considerably weakening, and the shift in the balance of power was not in Moscow’s favor.

The systemic factor of long-term Soviet decline was accompanied by harsher rhetoric from Washington. Reagan’s stance was not a matter of mere words; he sanctioned the placement of Pershing II and Cruise missiles in West Germany as well as the wide-scale renewal of US “ferret flights” to test Soviet radar and air defenses[xv]. To Soviet planners the juxtaposition of such data was alarming. With analysts believing that US Pershing-II missiles could reach Moscow within five minutes, the Kremlin leadership began to fear the possibility of a US first strike[xvi]. In May 1981, Andropov had initiated the joint KGB-GRU strategic monitoring program RYAN (Raketno-Iadernoe Napadenie– Nuclear Missile Attack) to monitor any preparations for any such US action[xvii].

In all of Cold War history, November of 1983 was perhaps the moment of greatest danger between the US and Soviet Union. On the heels of the White House’s spring initiation of the Strategic Defense Initiative and the tensions after the September 1st Soviet downing of Korean Airlines Flight 007, NATO had scheduled nuclear command exercises, code-named Able Archer 83, to be held from the November 2nd to the 11th. Judging from October telegrams from Moscow Center to the KGB’s London residency, Soviet attention was trained – with grave intensity – on the exercises as a potential prelude to a Western surprise attack[xviii].

While Euro-Atlantic leaders were largely unaware of the extent of Andropov’s alarm at the NATO exercises, miscalculations mistaken as war indicators might have triggered Soviet preemption – spearheaded by spetsnaz. As intelligence scholar Benjamin Fischer bluntly states, “The war scare was for real” during the early 1980s[xix]. Far from a product of some clinical paranoia, Soviet strategic culture was forged by historical experience. Hitler’s ability to launch Operation Barbarossa – due to Stalin ignoring numerous intelligence reports that a German attack was imminent – resulted in a war of annihilation. The Kremlin could never permit such a disaster again, and now the margin of error was measured in minutes. Andropov’s creation of KGB special operations units was well-timed: Alpha was the Soviet leadership’s shield, and Vympel its sword.

At the critical juncture of a crisis like Able Archer, Vympel’s combat groups would have deployed and infiltrated into the US and allied countries to near-simultaneously assassinate the enemy’s leadership and destroy vital command and control facilities. Suppressing NATO military-political coordination and additionally disabling its nuclear launch assets in the European theatre, groups of spetsnaz operators from both the KGB and GRU would have cleared the way for the surge of Warsaw Pact armor across the Fulda Gap[xx]. And before such a notion is dismissed as idle speculation in the style of Tom Clancy yarns, in the early 1980s the communications of the entire US Navy, the most potent arm of Washington’s nuclear triad, were an open book to Moscow thanks to the Walker espionage ring[xxi].

The prospective operations of KGB spetsnaz, in conjunction with those of the GRU, were designed to induce strategic paralysis in a hostile state and enable the Soviet Union to carry off an advantageous preemptive nuclear strike if necessary. It is not publicly known whether any such visitors filtered into Western capitals during November 1983 or other periods, but the likelihood is high. Developing such an elite unit capable of unique assignments must be evaluated as strategic foresight on the part of Yuri Andropov. A consummate practitioner of statecraft in the shadows, this master of the KGB appreciated the value that could be brought to bear at pivotal moments by a handful of specially trained men.

Lessons Learned?

We should all be grateful that cooler heads and providential restraint prevailed in the dark days of 1983, and that the signal for Soviet spetsnaz to commence action never came. Yet a generation later, we again find ourselves in a similar crisis: after the Soviet collapse NATO has pushed deep eastward. A resurgent Russia sees not only its sphere of interests, but also its sovereignty and very survival under threat. The nation that defeated Napoleon’s Grande Armee and the once-invincible Wehrmacht is again developing contingency options, from nuclear forces to cyber-warfare and spetsnaz. None of this renewed bipolar confrontation, however, is inevitable. If mutual respect amongst peoples is more than just rhetoric, men of good will can step back from the brink and make peace possible.

Works Cited

Primary Sources/ Interviews

Andrew, Chistopher & Gordievsky, Oleg. Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions. Stanford University Press, 1994. Stanford.

Drozdov, Yuri. Vymysel Iskliouchen. Vympel-Almanakh, 1996. Moscow.

Earley, Pete. “Interview with the Spymaster.” The Washington Post, April 23, 1995. http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-chat/695402/posts

Kryuchkov, Vladimir. Lichnoe Delo. Eksmo, 2003. Moscow.

Kuznetsova, Tatyana. “Razvedchik Spetsnaznachenia.” Argumenty I Fakty, August 16, 2006. http://www.fsb.ru/fsb/smi/interview/single.htm!id%3D10342720@fsbSmi.html

Samodelova, Svetlana. “Kogti Andropova.” Moskovskii Komsomolets, June 19, 2004. http://www.mk.ru/numbers/1136/article33242.htm

Secondary Works

Lubyanka 2: Iz Zhizni Otechestvennoi Kontrrazvedki. Mosgorarkhiv, 1999. Moscow.

Atamanenko, Igor. “Porkhaya kak Babochka, Zhalit kak Pchela.” Nezavisimoe Voennoe Obozrenie, July 31, 2009. http://nvo.ng.ru/spforces/2009-07-31/12_alpha.html

Boltunov, Mikhail. Vympel: Diversanty Rossii. Yauza/Eksmo, 2003. Moscow.

Campbell, Capt. Erin E. “The Soviet Spetsnaz Threat to NATO.” Air Power Journal, Summer 1988. http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/apj/apj88/sum88/campbell.html

Fischer, Benjamin B. “A Cold War Conundrum.” Center for the Study of Intelligence, 1997. http://www.cia.gov/csi/monograph/coldwar/source.htm

Kokurin, A.I., & Petrov, N.V. Lubyanka: Spravochnik. Izdatel’stvo Materik, 2004. Moscow.

Medvedev, Roy. Neizvestnyi Andropov. Pheniks, 1999. Moscow.

Prokhorov, Aleksandr, & Kolpakidi, Aleksandr. Vneshniaia Razvedka Rossii. Neva, 2001. St. Petersburg.

[i] Lubianka 2: Iz Zhizni Otechestvennoi Kontrrazvedki. (Mosgorarkhiv, 1999. Moscow), 304.

[ii] Medvedev, Roy. Neizvesntnyi Andropov. (Pheniks, 1999. Moscow), 188.

[iii] Atamanenko, Igor. “Porkhaya kak Babochka, Zhalit kak Pchela.” (Nezavisimoe Voennoe Obozrenie, July 31, 2009) http://nvo.ng.ru/spforces/2009-07-31/12_alpha.html

[iv] Kokurin & Petrov. Lubyanka: Spravochnik. (Izdatelstvo Materik, 2004. Moscow), 218.

[v] Samodelova, Svetlana. “Kogti Andropova.” (Moskovskii Komsomolets, June 19, 2004) http://www.mk.ru/numbers/1136/article33242.htm

[vi] Prokhorov & Kolpakidi. Vneshnyaya Razvedka Rossii. (Neva, 2001. St. Petersburg), 74.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid, 88.

[ix] Kryuchkov, Vladimir. Lichnoe Delo. (Eksmo, 2003. Moscow), 234.

[x] Drozdov, Yuri. Vymysel Isklyuchen. (Vympel-Almanakh, 1996. Moscow), 161.

[xi] Boltunov, Mikhail. Vympel: Diversanty Rossii. (Yauza/Eksmo, 2003. Moscow), 19-24.

[xii] Drozdov, Vymysel Isklyuchen, 170.

[xiii] Kuznetsova, Tatyana. “Razvedchik Spetsialnogo Naznachenia.” (Argumenty I Fakty, August 16, 2006) http://www.fsb.ru/fsb/smi/interview/single.htm!id%3D10342720@fsbSmi.html

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Fisher, Benjamin B. “A Cold War Conundrum.” (Center for the Study of Intelligence, 1997) http://www.fsb.ru/fsb/smi/interview/single.htm!id%3D10342720@fsbSmi.html

[xvi] Andrew & Gordievsky. Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions. (Stanford University Press, 1994. Stanford), 74.

[xvii] Ibid, 67.

[xviii] Ibid, 86.

[xix] Fisher, “A Cold War Conundrum.”

[xx] Campbell, “The Soviet Spetsnaz Threat to NATO.”

[xxi] Earley, Pete. “Interview with the Spymaster.” (The Washington Post, April 23, 1995) http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-chat/695402/posts

Wow, awesome site!

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Blinded by the Darkness and commented:

Very interesting and gives some context to the current situation … great photos too.

LikeLike

Thank you, Neo-Pelagius.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was a very fascinating read, very enlightening. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person