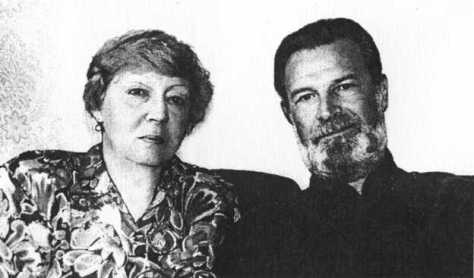

KGB officer Vadim Nikolaevich Sopryakov – “Comrade Maxim” – tells of a key recruitment he made in 1968 while serving under diplomatic cover in Delhi, India. Sopryakov, a retired captain first rank, began his service in the KGB Border Guards naval units, then transferring to the First Chief Directorate (Foreign Intelligence), and even serving in the elite Directorate S (Illegals) and spetsnaz. In his account of his time in India, Sopryakov sheds light on the practical psychology applied by an intelligence officer for recruiting potential agents, in this case “Mr. B.,” whom the KGB would code-name “Herman.”

On the next-to-last day of a 1967 coming to its end, the Soviet intelligence resident in Delhi received an assignment from the Center:

Pinpoint individual “B.” Collect characteristics on him. Determine the expediency and practical possibility of his development for recruitment. Report on results.

Within the message was also mention that the lead on Mr. B had been received from “Michele.” A longtime vetted agent of the KGB, Michele had met several times with the Indian during a business trip through a number of West European countries. Michele’s professional flair suggested to him that Soviet intelligence would definitely be interested in Mr. B. And not only because of his high position in India’s leadership circles, but most of all because of his widespread contacts with Americans, of whom he wasn’t fond in addition.

The resident’s resolution on the message was extremely short: “To Comrade Maxim for execution.” “Maxim” was one of the operational pseudonyms of now-retired Captain First Rank Vadim Nikolaevich Sopryakov.

***

Why did the choice fall on you? You had just arrived to the Delhi residency in August. You probably didn’t have time to orient yourself as necessary. Or was that the way they welcomed newcomers?

The mission to recruit Mr. B was dumped on me during my fifth month of work in Delhi. I managed to learn the city and select verification routes to detect hard-bitten Indian surveillance and evade them. I marked places for clandestine meetings, and, moreover, I already had two valuable agents I was handling. One of them was local, a high-level government official. The other was from the diplomatic corpus, a leading diplomat of one of the accredited embassies in Delhi. Working with agent networks wasn’t new for me, and therefore business with them got started well. Information came regularly and got a sufficiently high evaluation at the Center; the resident was satisfied. But I didn’t have my own recruitment in development, since I hadn’t managed to obtain one. That’s why he “tossed” the lead my way.

So it turns out that you came to Delhi as an already experienced field operative. Where and when did you acquire this experience?

Before India I had worked for four years in the Burma residency in Rangoon (now Yangon). This was my first assignment abroad, my baptism by fire, so to speak. I stayed satisfied with how it went. It’s also true that “Lady Luck” played no small role in that.

In the center of Burma’s capital were scattered several lakes. On the picturesque bank of one of the largest ones, Inya Lake, was founded the international Rangoon Sailing Club for yachts. Since I’m a naval officer, I sailed rather often, and I was made to be in that club.

I have to say that Inya is a capricious lake with its own personality. With its powerful unbridled winds that often changed direction, it was capable of confounding even the most experienced yachtsman.

Once two French diplomats had fallen victim to Inya – a gust of heavy wind had overturned their yacht in a second’s time. I hurried to the rescue. I picked up one of the victims, and the second I asked to stay next to the capsized yacht and wait for rescuers. That was required by club rules.

Having brought the Frenchman to shore, I offered him a dry towel and invited him to the bar. Two or three portions of whiskey calmed him down somewhat, and he relaxed. On his face there appeared a smile. He introduced himself, and for some moments I had to endure a light shock. Rene Milier was the new, and yet to have been accredited, French ambassador in Burma (now Myanmar). Lady Luck was providing me a chance, and what a chance it was!

After a drawn-out friendly conversation, Rene Milier asked, “if it wouldn’t burden me,” to drop him off at the French embassy. Do I need to say that I did this with great pleasure?

From that moment until the end of my tour of duty, I would without fail receive invitations (along with my spouse) to all official receptions and other protocol events that were arranged in the French embassy, or, in a more narrow circle, at Rene Milier’s personal residence. He even obligatorily invited me on familiarization trips around the country. Thanks to all this, my sphere of connections in the diplomatic corpus at the level of ambassadors and advisors, as well as among leading officials of the Burmese foreign ministry and others, expanded incredibly. And that meant that my search for sources of information and candidates for recruitment was made easier.

Also, in the Rangoon residency, as in Delhi, no one was given downtime. Two weeks after my arrival in Burma, I was transferred for handling the first agent in my life. He was a local citizen. He provided operational information on Americans, in particular on contacts with Burmese officials.

As soon as I set up work with him, I was tossed another agent, also from the locals. But this one occupied a rather solid position in one of the government structures and passed us political information, about the Americans, by the way, which was rated sufficiently highly in the Center.

And that’s how I acquired experience working with agents. Simultaneously my work against the Americans was being sketched out, who at the time were the “main adversary.” My specialization in the main adversary was consolidated after I managed, again thanks to Rene Milier, gain access to a major political figure in Burma – “Dan,” as I christened him. This was my first recruitment, and it took a whole year of Dan gradually being brought into cooperation with our service. At the very beginning I limited it to obtaining spoken information on Burmese-American bilateral relations. Then I began requesting written explanation of information and his opinion on one or another aspect of Washington’s regional policy in Southeast Asia. And ultimately I brought him to see that it was most practical for him to pass me documents.

Dan’s fruitful partnership with our service also continued after my departure for the Motherland, right up to his retirement.

So I think that my Burmese experience plus my orientation of work against the Main Adversary influenced the resident’s decision to assign me to figure out the lead on Mr. B.

And what did you start from? After all, India isn’t Burma. Isn’t that the case?

Yes, there were two major differences. India immediately struck me with its scale and energetic political and socio-economic life. My first love, Burma, looked like a province in India’s context, where political and diplomatic life hardly had a pulse.

I was also at first surprised by the operational environment in Delhi. On the one hand, everywhere you could hear “Hindi-Rus bhai, bhai!” – “Long live Indo-Soviet friendship!” On the other, from my first day I was under the dense coverage of local surveillance. Wherever I went, with my wife or alone, surveillance cars accompanied me without fail. In the stores, at the bazaar, or simply outside – everywhere were people who imposingly introduced themselves to me, attempting to find out as much information as possible about me and my acquaintances, even random ones. I understood that my Burmese “friends” from CIA and SIS took care to orient Indian counterintelligence about me in a timely manner, as well as about my time in Rangoon, and apparently they relayed their suspicion that I belonged to the KGB. I had only to take all this into account and behave accordingly.

Now about the assignment on Mr. B. To “establish” in our operational language means to clarify where and with whom the target lives, and also where he works and what he does. At the moment of my receiving the assignment, Mr. B. was wasn’t known to the residency; no one from the operational staff had even heard his name. We had to turn for help to our agent network. We found out that Mr. B. had entry to a circle of quite influential politicians. He appeared at official events and even state receptions extremely rarely.

Finally, we learned that Mr. B. was very suspicious of Americans, but he carefully hid it, since by the nature of his service he maintained working contacts with them.

Even this far-from complete-information was wholly enough to recognize that “Herman” (as we named Mr. B.) presented, as we would express it, “undoubted operational interest.”

Also obvious was the necessity of me establishing personal contact with him – introduce myself, that is. But I needed to do it in such a manner that it would in no way expose our interest in him either to local counterintelligence or, God forbid, the CIA or SIS. Yet where and how would I make my approach to this hermit?

A suitable occasion presented itself approximately a month later. Our acquaintance occurred on neutral ground, as if it was unforced. And the main thing was that Herman not only didn’t avoid contact, but he also, it seemed to me, demonstrated interest in continuing an acquaintance with a Soviet representative.

And again the same conundrum – how could I develop our contact? We thought a long time, and the resident and I agreed that even within a circle of people loyal to Herman, my communication with him would inevitably beget the legitimate question: where did this Russian come from, and why is he here? That would be fraught with unpredictable consequences. There was only one option left: direct “cold pitch” recruitment, i.e. a frank offer to Herman on cooperation with our service. We took into account that he might refuse; after all, we couldn’t figure out for the life of us his true political convictions. At the same time we weren’t worried that if in the case of refusal he’d decide to create a scandal, since the offer on partnership would be made one-on-one, without witnesses.

From Comrade Maxim’s operations brief:

In accordance with the approved plan, I undertook a one-on-one meeting with Herman. The discussion continued nine minutes. Herman heard out my proposal silently, showing envious composure. Not one muscle on his face twitched, although my offer was clearly unexpected for him. Only for a moment his eyes shot toward me, and in them I captured just slightly the surprise. After some thought, nodding his head, he pronounced: “Well, you guys are risky!” Then he looked at me fixedly and added:

Alright. Here on my business card is my home address, where I live only with my spouse. If you’re so brave, come tomorrow at midnight. There won’t be any servants in the home. But you should appear at my place together with your wife. I’ll be waiting for you there. And now you must excuse me, I have to get ahold of myself after your surprising proposal.

He gave me his business card and we bid each other farewell.

As you noted in the report, Herman listened to your recruitment pitch with “enviable composure.” It’s true he also then admitted that he had to “get ahold of himself.” How did you feel at that moment?

I was soaked. I was covered in sweat from my head to my feet. I felt streams of sweat flowing down between my shoulder blades to my waste, and how my knees were stuck to my pant legs. And that was despite it being cool in the room – the air conditioner was on.

I started coming out of my petrified state when Herman passed me his business card and offered to meet me at his house. I hazily remember how I ended up outside, took a taxi and reached the hotel where my colleagues were expecting me.

At the embassy the resident was awaiting me impatiently. I didn’t manage to open my mouth as he shook my hands with the words: “Looking at your unscathed face, I see that everything went successfully.” And then he somehow noted: “Your physiognomy just radiated the joy of victory.”

From Comrade Maxim’s operations brief:

At the time appointed by Herman, my wife and I walked up to his house on foot. He met us warmly. I introduced my wife. While the women were engrossed in conversation, Herman took the initiative and invited me to “smoke” in his office. Herman also wasn’t rushing to wrap everything up. We exchanged opinions on events in international life, on India’s policy on the subcontinent, and on relations between our countries. Finally Herman began speaking on the main subject, beginning from his wish to spend a few more meetings with me in his home in order to size me up better and decide for himself the question of the practicality of working namely with me. “Although,” he emphasized, “in principle I’ve already made the decision. Now I must affirm for myself the idea that I am acting correctly.” Without lingering, I agreed to his offer of spending a few more meetings at his house.

Comrade Maxim and his wife were to pay night visits to Herman another five or six times before the latter would join the list of agents personally recruited by the Soviet captain, third rank.

“During one of the final night visits,” Vadim Nikolaevich remembers, “a dangerous incident took place. Somewhere around two in the morning, a courier from the presidential palace unexpectedly arrived at Herman’s house. At that time we were still drinking tea in the sitting room. As always, Herman was unflappable, but I tensed up, as this unexpected visit could bring about tragic results. Our host accompanied the courier through the sitting room to his office. As he was walking, he took the sealed envelope from him, and passing by us, mentioned to the courier that these were dear guests from Sweden. And that’s it. A minute later they came out, and the courier left.

Herman was calm, and in the presence of the women he said that it had been an ordinary messenger who hardly paid any attention to the foreigners in the house, inasmuch as there was nothing unusual about it. To my question of whether we looked like Swedes, with a smile Herman answered that my wife Lydia was a striking blonde, and therefore he said she and I were Swedish. For a messenger Sweden was somewhere far away in the snow. The important thing was that we weren’t from the United States or England. If Herman had said we were Americans or Britons, then that might have remained in the courier’s mind, but neutral Sweden would hardly stay long in his memory.

Somewhat later I clarified with Herman that this unexpected arrival didn’t have any consequences. ‘The messenger forgot about everything,’ Herman waxed ironic, ‘as soon as he exited my house.’

A bold question: did you pay for Herman’s cooperation?

Unconditionally no! In his partnership with us he saw a direct benefit for India. If it was to the contrary he would have told us to go…far away. And we wouldn’t have dared to make him the offer.

Work Translated: Жемчугов, Аркадий. Шпион в окружении Андропова: Разведка в лицах и событиях. М: Вече, 2004.

Translated by Mark Hackard.

Reblogged this on Jay's Analysis.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on – Thoth Experiment – and commented:

First hand account of how the KGB recruited and operated in Burma and India.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great piece! Reblogged this on thothexperiment.wordpress.com

LikeLiked by 1 person