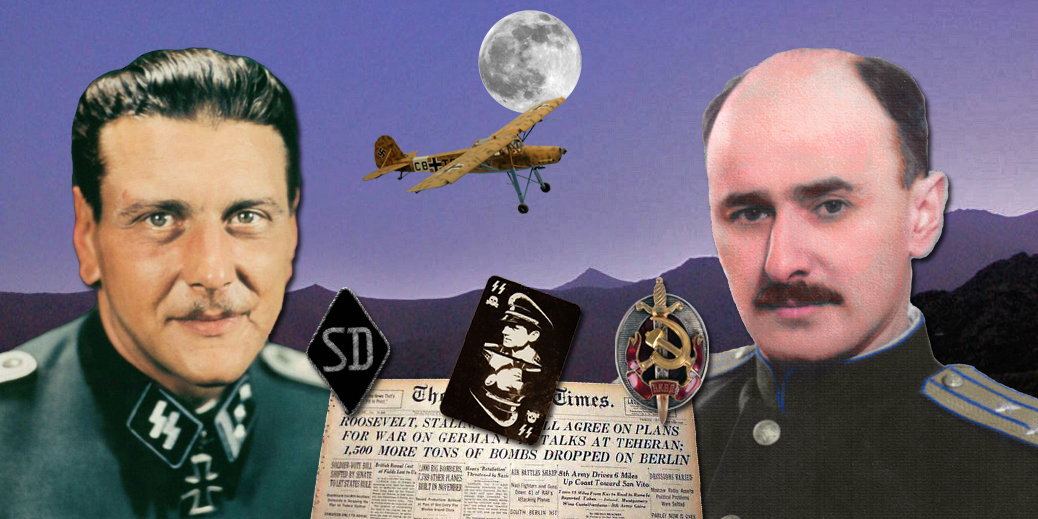

In late 1943 SS commando Otto Skorzeny, known as “the most dangerous man in Europe,” was tasked by Hitler with a daunting mission: kill Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill, the Big Three, in Tehran, Iran. The bold plan, code-named Unternehmen Weitsprung (Operation Long Jump), might even have succeeded but for the efforts of Allied intelligence services. Below is the story of Ivan Agayants, Soviet NKVD resident in Tehran, who played a key role in foiling Berlin’s assassination plot.

In the old Soviet action film Tehran-43, the fearless and sexy intelligence officer sent from Moscow to Iran’s capital with a special mission dashingly neutralized Hitler’s terrorists, who were preparing the assassination of Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill. In that film there are three truths. The first: At the end of 1943 in Tehran, the Big Three Conference took place. The second truth: the fascists were preparing an assassination attempt on the leaders of the USSR, USA, and Great Britain. And the third: Soviet intelligence liquidated the terrorists.

But there’s one untruth in the film: this antiterrorist operation, which became a classic one, was executed not by a Fatherland-style James Bond, but by our intelligence resident in Tehran, Ivan Ivanovich Agayants. A man who by his outer appearance in no way looked like a super-spy: thin, tall, worn out by tuberculosis, with a quiet voice and hurried gait, he sooner looked the part of a professor, musician, or lawyer. He had a Walther with his name engraved on it, and also shot excellently at the range, but not once in life did he use his pistol for “business.” His weapon was a thorough knowledge of the art of intelligence, the ability to orient oneself at a moment’s notice in any circumstances, and to profoundly analyze them from all angles, evaluate, and make the most rational decision. And his achievements aren’t limited to his Tehran period.

***

On an August day in 1943, Soviet intelligence resident in Tehran Ivan Agayants received an order from Moscow to immediately fly out to Algiers under the passport of a USSR representative on the Repatriation Commission with the name Ivan Avalov and participate in organizing USSR representations attached to the French National Committee (Comité national français – CNF).

This was the official version of the trip, or, as they say in intelligence, the legend. In reality the Soviet intelligence officer was given the assignment to figure out what the FNC under de Gaulle represented, what real powers stood behind it, and what were the chances of de Gaulle becoming France’s national leader. It was also necessary to clarify the general’s views on the postwar arrangement of Europe and the character of his relations with the Americans and British. And also, of course, to take interest as to what US and British intelligence were doing in Algiers and what were there positions in the CNF.

Who are You, General de Gaulle?

The immediacy of the assignment, just as its importance, were explained sufficiently simply. In another month the Big Three Conference would open in Tehran – with Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill. And one of its key issues was considered the postwar ordering of Europe.

Stalin possessed reliable intelligence information on how postwar France would be envisioned in Washington and London. He also knew that the Americans were placing their bets on General Giraud, and with his help they were attempting to gain control of the French Resistance and establish military and political control over North Africa – Algeria, Tunis, and Morocco, French colonies. The Americans considered the main obstacle on the path to reaching these objectives to be General de Gaulle. And therefore, with the English, they did everything possible and impossible, as Anthony Eden expressed, to “not give de Gaulle the slightest chance of creating a unified French government before the Allied landing in France, moreover to form a government, since by that time he’d be unable to remove from power.”

Stalin knew all of this. But he had hazy representations about General de Gaulle himself, his real possibilities, and his attitude toward the Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain. It behooved Agayants to fill in this essential blank spot.

On September 3rd, 1943, I visited General de Gaulle upon his invitation. At the beginning of the conversation he took interest in the situation on the Soviet-German front, and attentively hearing me out, noted that the Germans still possess sufficiently large reserves. And right then he emphasized that he was sure of the Red Army’s victory, since it had many advantages.

In relation to the landing of Allied forces in Calabria, de Gaulle noted, not without irony, that military action there was conducted in a fashion not shabby or shoddy, since there were ‘very high mountains.’ And already in full seriousness he continued that allied forces for the first time had to clash with German divisions. And although those divisions had recently been subjected to powerful blows in Sicily, they were obviously still strong enough to oppose Anglo-American forces.

Concerning the CNF, de Gaulle quite optimistically evaluated its current position and near-term prospects. Along with that, he added that the opening of a Soviet representation attached to the Committee bore witness to the genuinely friendly intentions of the Soviet government with respect to France, facilitated the strengthening of French unity, and provided the Committee and opportunity to decisively oppose American interference in its affairs. Frankly recognizing the presence of serious disagreements with Giraud, the general expressed firm resolution to remove all his political opponents from their posts, including Giraud. In his words, just today a Committee session had taken place, and the decision had been taken to hand over Petain and his supporters to justice at the first opportunity. ‘Let’s see now if the Americans and Giraud would dare do bring the Vichy men to Algeria,’ de Gaulle concluded.

Then he crossed over to the matter of principals of Europe’s political organization after the war. He thought that Europe should be based on friendship between the USSR, France, and Britain. But the primary role should have been played only by the USSR and France. But Britain, as a great power, had its interests mainly outside of Europe. Therefore, it should be engaged first and foremost in non-European problems. Concerning the United States, in the general’s words, they also could not stand aside from the resolution of international issues. ‘Nonetheless, Europe’ – as if he were summing it up – ‘should define itself. We should also organize organize postwar Europe. Jointly, it will be easier for us to decide Germany’s fate.’

Already bidding farewell, de Gaulle acquainted me with one of his relatives, a young French intelligence officer who had recently arrived from Germany, where he met with an officer who had been in the German concentration camp in Lubeck. In his words, Josef Stalin’s son is confined in this camp. He was holding up well, although he has been subjected to mockery and torture. According to de Gaulle, there is the possibility of setting up correspondence with Stalin’s son through his people. I thanked de Gaulle for this message.

Avalov

Two days later a second information report from “Avalov” arrived in Moscow. Then a third, a fourth, a fifth… And each of them were accounted for not only in the position of the Soviet delegation at the Tehran Conference, but also, what is much more important, during the identification and development of Soviet-French relations after the war.

Returning to Tehran from Algiers, as the head of the residency, Ivan Agayants had already been included into preparations for the meeting of the Big Three, first and foremost for ensuring its security.

Preparing to Jump

Long Jump. Such was the code name of the commando-terrorist operation that was developed in the strictest secrecy at a top-secret SS base in the Danish capital of Copenhagen.

“We’ll repeat the jump in Abruzzo. Only this will be a long jump! We’ll liquidate the Big Three and turn the course of the war. We’ll kidnap Roosevelt so that it will be easier for the Führer to reach terms with America,” boastingly announced one of the designers of the operation, SS Sturmbannführer Hans Ulrich Von Ortel. The designation of this difficult-to-reach place in the Italian Alps circulated the entire world press after Mussolini, overthrown by the Italians, was whisked away and brought to Germany in a special Fieseler Storch airplane in July of 1943.This operation, unique in its own way, was brilliantly executed by SS Sturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny, whom Nazi propaganda called an idol of the Germanic race. When the idea for “Long Jump” was born in Berlin, the choice naturally fell upon Otto Skorzeny. But here the idol of the Germanic race didn’t get lucky. He was outplayed by Ivan Agayants.

“On November 20th, 1941, packing all our things into our suitcases, we got onto an old bomber that was to bring us to Tehran,” Elena Ilyinichna, Agayants’ spouse and partner in battle.

However, sitting down in the plane was an elastic conception. Since I was expecting a child, I situated myself on that the accommodating pilots had set in the bomb compartment. Ivan say Turkish-style over the bomb bay, which caused no small number of jokes and enlivened the flight. Over the Caucasus our plane was shot at, but everything came out safely.”

The first month we lived in the house of Andrei Andreevich Smirnov, the Soviet ambassador in Tehran. We were placed in a somewhat dark entryway where an old couch stood. On it was born our daughter, Acha. Ivan Ivanovich and Kolya, my son from my first marriage, slept on the floor. The ambassador invited Ivan Ivanovich to his quarters, but he didn’t want to leave me alone. Finally we were allotted two rooms and everything shook itself out.

Agayants began his activity as Soviet intelligence resident in Tehran with the detailed study of the local situation, and he went to the intelligence leadership with a proposal to fundamentally reevaluate all of the residency’s work. “Our apparatus,” he wrote in his report to the Center, “is loaded down with work with materials and agents that nevertheless don’t shed light on issues of political intelligence and don’t answer to the everyday needs of our diplomatic and political work in the country. Neither political information on phenomena of the country’s internal and external life nor work on these materials are the main content of the “office’s” activity… Here we are occupied primarily with matters of security and counterintelligence, which bring our agent-operational work closer to the tasks of our internal organs.”

The critical analysis of the residency’s activity was reinforced in the report by an extensive plan for its reorganization and shift toward offensive intelligence work. The resident’s initiative caused an ambiguous reaction in the Center. After all, in Tehran residency alone there were several dozen operations officers, and just as many in the eight sub-residencies active in other Iranian cities. And Agayants was proposing re-making this machine all over again. Was Agayants, who had barely just turned 32, up for it? Nonetheless, although with some qualifications, the resident’s proposals were approved.

Receiving the “go” from the Center, Agayants undertook a stringent “revision” of the agent apparatus he inherited. Due to a lack of need, many agents were excluded from the network. However, a decision on each of them was taken after a thorough weighing of all pros and cons. For example, Vera, recruited in Stockholm and the wife of a high-level official at the Iranian embassy there, was part of the agent apparatus. At that time in Sweden, she rendered Soviet intelligence tangible assistance. When she returned to Tehran, she confirmed her readiness to continue the partnership. Her intelligence possibilities, however, were seen as extremely insignificant by the residency. By the time of Ivan Ivanovich’s arrival, the time had come for a decision to refuse Vera’s services. In particular, the intelligence officer who handled her case insisted upon this during the “revision.” Agayants spent several evenings with him before convincing him to use Vera’s proximity to the Shah’s family, especially to the older princess, in the interests of Soviet intelligence, as well as the official position of her husband, who occupied a rather high post in the Iranian foreign ministry and was under his wife’s thumb. His urging, as it turned out, wasn’t in vain. Soon important information on the Shah’s foreign policy plans began flowing from Vera, as well as operational intelligence that facilitated the acquisition of agents in the leaderships of the leading political parties, the state bureaucracy, and even in the Shah’s inner circle.

Agayants dedicated special attention to the creation of dependable agent positions in the higher echelons of Iran’s army. “We cannot and must not limit ourselves only to sources of information. It is important to access development targets, who, aside from information we need, would also possess significant influence in the army and officer corps and would be courageous and decisive in practical action,” he instructed the residency’s staff. And soon “their people” appeared next to the war minister, in the leadership of army intelligence and other special services, and among the Shah’s advisors. Henceforth reliable information not only on the plans and intentions of the Iranian government went to Iran, but also information on the measures planned by the residency to ensure the security and integrity of strategic shipments (tin, rubber, etc.) flowing to the Soviet Union from the Persian Gulf region through the ports of Dampertshah, Bushehr, and Qar. Reliable agent control was established over all key points on Iran’s borders with the Soviet Union, Turkey, and Afghanistan.

The British intelligence station was also taken under firm control; as was ascertained, it was engaged in activity far from friendly in relation to the Soviet Union. It was headed at that time by Oliver Baldwin, the son of Great Britain’s former prime minister. The British demonstrated an enviable activism in building bridges with anti-Soviet nationalist organizations active in the deep underground on the territory of Soviet Armenia. With that objective they sent the experienced intelligence officer Phillip Thornton across the Turkish-Soviet frontier into Armenia. He was ordered to make contact with the leadership of the Dashnaktsutyun and make an agreement on cooperation. The British didn’t suspect that this visit allowed the Tehran residency to discover the chieftains of the Dashnaktsutyun, establish their places of residence, and get a clear idea of this organization’s structure, the principles of joint action among its branches, and its communications channels. The rest, as it’s said, was a technical matter for the USSR state security organs’ internal units.

Jump, Interrupted

Agayants was dealt a special headache, of course, by Germany’s intelligence services, which had firmly entrenched themselves in Iran largely thanks to the elderly Shah’s sympathies for Hitler.

In the Tabriz region, in particular, Berthold Schultze-Holtus’ group was active. This Abwehr station chief at first acted as the German consul in Tabriz in a fully official capacity. But then he went underground, transforming into a mullah with a beard red from henna. In the summer of 1943, not long before the meeting of the Big Three, from Berlin he received the order to settle in with the Qashqai tribes around Isfahan. Soon paratroopers from Otto Skorzeny’s team were dropped there, and they were equipped with a radio transmitter, explosives, and an entire arsenal of all possible weaponry.

Almost simultaneously with Schultze-Holtus, Gestapo station chief Franz Meyer, who group was active in direct proximity to Iran’s capital. Meyer himself turned from a German businessman into an Iranian farmhand working as a gravedigger at an Armenian cemetery. On the eve of the Tehran Conference, he was also sent six of Skorzeny’s SS paratroopers.

Schultze-Holtus and Meyer maintained constant communications with Berlin and between each other, while they coordinated their everyday work with Müller, the Abwehr’s main station chief in Tehran.

Such were the main links of the mechanism intended to ensure the successful execution of Operation Long Jump. Otto Skorzeny, of course, didn’t suspect that his every move was tightly monitored by Ivan Agayants, and that with the coming of “Day X,” Schultze-Holtus and Meyer’s groups would be taken out of the game at lightning speed. And there wouldn’t be any jump.

With Müller such a story came to be: Possessing information that this Abwehr ace had long been studied by Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), Agayants offered the British to combine their efforts. From a mutual consensus it was decided to not touch Müller a while longer in order to discover his agent network and all his connections in the Iranian establishment. This gentlemen’s agreement, however, was violated by the British, who, not even informing their Soviet colleagues, seized Müller literally a day before the Tehran Conference began its work.

Information on Long Jump was brought by Vyacheslav Molotov to Averell Harriman, then-US ambassador in Moscow, who was part of the American delegation in Tehran. Simultaneously Stalin’s offer for Roosevelt to stay in the Soviet embassy – for security considerations – was relayed. The American president accepted the proposal, to Churchill’s obvious dissatisfaction. Roosevelt, after all, had been offered to stay in the British embassy, the territory of which adjoined the Soviet one. But the British proposal remained without an answer.

In the course of one night several rooms were furnished for Roosevelt and his service personnel in the Soviet embassy’s main building, to where he immediately moved. “During the Tehran Conference,” recalls Elena Ilyinichna, “Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov, and Mikoyan were situated in our rooms and the ambassador’s apartment. A special facility was prepared for Roosevelt. Our family moved over to the apartments where the Shah’s harem was at one time. It was around 500 meters to the house in which the sessions were underway. I worked at the conference as a stenographer…”

On one of the days we were brought to our feet. During the negotiations in the conference hall, Roosevelt wrote something on a sheet of paper and through his assistant passed it to Churchill. Churchill read it, wrote an answer, and then passed the note to Roosevelt. Stalin didn’t show dissatisfaction, but immediately after the negotiations, he called in Ivan Ivanovich and ordered him to move heaven and earth to get a hold of the accursed note in order to uncover the ‘secret correspondence.’ They found the paper and reported immediately. ‘Sir! Your fly is unzipped,’ was written in Roosevelt’s handwriting. Churchill answered: ‘The old eagle won’t fall out of the nest.’ Stalin was very pleased that the Anglo-American collusion was limited to such an innocent subject. Roosevelt, by the way, didn’t once go to Churchill’s residence. The entire time he stayed on the territory of the Soviet embassy.

From November 28th to December 2nd, the Tehran residency was working 24 hours a day. The entire agent network was activated. All information meriting attention Ivan Ivanovich expeditiously reported to “Uncle Joe” himself. Soviet intelligence officers solved their professional problems themselves. “Even I had to participate in dramatic measures to liquidate enemy agents,” admitted Elena Ilyinichna. Elena was not just the wife of the resident, but also an operations officer who completed her 20 years of service in foreign intelligence at the rank of colonel.

One such operation was carried out jointly with our military. I remember how one of the most malignant foreign agents who was acting against us in Tehran suddenly began enthusiastically courting me. Our military intelligence received the assignment to take him out of the game. We jointly developed a plan for my ‘date’ with him, during which I was supposed to throw a specially sewn bag over my admirer and tie him up. Then I was to deliver him where he needed to be by automobile, which was also done.

Ivan Agayants worked in Iran until the spring of 1946. Periodically he would travel to Algeria for meetings with General de Gaulle and his closest fellow officers. He also carried out Moscow’s other assignments, including rather delicate ones. In particular, he had the occasion to visit Kurdish-populated regions of Iran several times incognito. The Kurds had raised a rebellion against the Shah’s regime, and at the same time had declared Moscow their enemy, as the USSR was friends with the Shah. As a result of substantive and skillfully executed discussions with influential elders and religious leaders from the Kurdish tribes, Agayants completely cured an unnecessary “headache” for Moscow.

Work Translated: Жемчугов, Аркадий. Шпион в окружении Андропова: Разведка в лицах и событиях. М: Вече, 2004.

Translated by Mark Hackard.

Reblogged this on TheFlippinTruth.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Jay's Analysis.

LikeLike