Leonid Sergeevich Kolosov (1926-2008) was a Soviet international correspondent for Izvestia and also attained the rank of lieutenant colonel in the KGB First Chief Directorate (FCD). Kolosov was stationed in Italy, his country of specialization, in the 1960s and 1970s under journalistic cover. In this interview he recounts his work with Sicilian mafia boss Nicola Gentile and penetrating the Red Brigades.

Leonid Sergeevich, how did you get into intelligence work?

I got into intelligence work by accident, but the secrets of this service’s techniques were revealed to me by my instructor when I was learning the mysteries of this complex but rather fascinating and interesting, work in Balashikha, a town outside Moscow, at the 101st School. In this school there were one-year and three-year training courses for intelligence officers. I made it into the one-year course.

Before enrollment in the school, I happened to have worked five years in Italy, in the economic department of the USSR Trade Representation, as director of the economic group. There were only three employees, including me and the secretary. During this tour I developed good connections among the country’s business world, I traveled across all of Italy, and I was acquainted with the president of Fiat, Vittorio Valleta, at a time when our country was sealing various economic agreements.

When I returned from my five-year tour, I was immediately accepted for work in the Ministry of Foreign Trade, in the directorate working with western countries. I worked as the senior consultant in a group that had been created back under Mikoyan. And then one day the secretary of our party committee Tutushkin, my good acquaintance from work in Italy, where he had headed the Trade Representation, called me on the phone and asked me to step into his office, saying that someone from the security organs wants to speak with me one-on-one. And this man, with the last name Akulov, having explained to me the difficult situation in foreign intelligence after Beria’s execution, asked me if I’d like to transfer into this unit since they were experiencing personnel problems. Not expecting such an offer, I naturally lost composure and asked him: “And what would I be doing?”

He answered that they’d teach me everything. And when I requested time to think it over, he said, “What is there to think about, really, do you agree or not?”

With these words his eyes grayed, and he became rather stern. And I understood: no, it’s better not to tell him. After which he explained to me that I would go to Italy under the cover of a deputy at the USSR Trade Representation, and I would work for the First Chief Directorate (FCD) of the KGB. The Minister for Foreign Trade, Patolichev, had already given his assent to my transfer into intelligence and signed off on my assignment; therefore, he advised me to not think it over for too long. I answered Akulov: if so, then so be it. Then he said that on August 30th, I’d need to drive up to one of the metro stations, where a bus would take me to intelligence school, where I’d be studying for a year. Moreover, he informed me that the atmosphere in the Institute was relaxed, and there was even a bar where you could have a drink – but don’t get carried away because they’d be vigilantly watching.

Akulov recounted my biography in more detail than I knew. And for them the main thing was that there were no Jews in my father or mother’s lineage; this was considered a very important factor in approval for intelligence work. My entry into the party at a young age also played a role.

They promised me my salary would be the same as I had in the Ministry of Foreign Trade. That made me extremely happy, since they paid us more in Mikoyan’s group than other officials of our ministry. When he took interest in my rank – I was a lieutenant after graduating from the institute – he said that they couldn’t raise it for me further, and I’d have to earn my next rank myself. And in nine years I served from lieutenant to lieutenant-colonel. They skipped me one rank, incidentally.

Since there was a relaxed atmosphere in intelligence school, I organized a theatre group. We studied in the school over the course of the week, and we were allowed home on weekends. I knew all the disciplines effortlessly; moreover I was a candidate of economic sciences. Aside from Italian, I was fluent in French, and the Italian language instructor said I knew it better than she did. After graduating from intelligence school, which I did with excellence, I worked one year in KGB FCD central apparatus.

And in that year, as a candidate of economic sciences, I began to write articles on economics for various newspapers. Pravda, in particular, published my articles on Italy. Some of my work was printed in Ogonek and Komsomolskaya Pravda. One day the chief of my department called me into his office, and showing me my articles, said: Why the hell should we send you to Italy as a trade representative? It’d be better for me to use journalistic cover, since in his opinion, that was the best cover for an intelligence officer. I objected that I had never done any serious journalism. Then, picking up the telephone from the government communications line, known as the “chopper,” he called the then-chief editor of Izvestia Aleksei Adzhubei.

Calling him Alesha since both their families were friends, he said that he had a “cadre” and an empty posting an Italy – so could Adzhubei accredit me in his newspaper’s international department? I was already at the newspaper the following morning, and papers with my articles were lying in front of Adzhubei on his desk. He reacted positively to my journalism, but he noted that my articles were rather boring and informed me that in a month I’d go to Italy for his newspaper’s international desk. But at the desk they didn’t always love outsiders, and there were plenty of claimants on the Italian trip. He told me, for that reason, to not skimp on money and host my future colleagues at a restaurant. I followed his advice, and afterward I established good relations with them. And no one envied me for going to Italy in a month’s time as the staff correspondent for Izvestia.

Before my departure, Aleksei Ivanovich told me about how they already had experience providing journalistic cover to our intelligence service. Before me a guy had worked under this cover, and he didn’t write anything. Italian counterintelligence quickly identified him and expelled him from the country. Therefore, I had to make myself known. Adzhubei’s paper was state media, and everyone knew that his father-in-law was General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev. Izvestia was bold, and it was allowed to do a lot. Aleksei Ivanovich told me that upon my arrival in Italy I should interview a prostitute, since it was an acute social topic in this country, while in the USSR, many Italian artistic films on this subject had been shown at the time.

And I had to interview a representative of the oldest profession so that she’d tell me how she found herself working the streets. Adzhubei warned me not to even think of engaging her services; otherwise I should just leave my party ID on his desk. This proposal from the main editor of Izvestia caused tremendous surprise to my resident. Although he said: “If Adzuhbei himself ordered it, then do it. But watch out so that their surveillance doesn’t catch you with her.”

And I did indeed interview a prostitute, paying her money. When she asked me who I was, I answered that I was a Pole, and paid her value on credit – twenty dollars. She told me about her banal fate. When the interview was over, she asked me: and what about love? I responded that since I’d be writing all night, I had no time for that. We could do that another time when I came to Italy.

To which she responded, exiting the vehicle, that I was either impotent or out of my mind. My interview with the representative of the oldest profession was printed in the newspaper Nedelya on a full spread under the title “Cast into the Streets.” And after this interview was reprinted in all the Italian newspapers, I was treated positively as a Soviet journalist. In all the years of my work in this country under cover as Izvestia’s staff reporter, Italian counterintelligence couldn’t unmask me.

Leonid Sergeevich, what was the division of labor for Soviet intelligence activity in Italy? What section fell to you?

In those years our intelligence had several lines of activity. There was Line GP (Glavnyi Protivnik) – the Main Adversary. That’s when our officer in any country was working against the Americans. Line PR (Politicheskaya Razvedka) – Political Intelligence – engaged in the selection of agent networks against the CIA, planning various actions against them. That’s where your humble servant also worked. We collected information on what was happening in Italy. There was a strong communist party in the country, and they told me I wouldn’t be working on that. We didn’t recruit communists; we only had friendly relations with them. I managed to interview the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Italy Palmiro Togliatti, after which we formed a most confidential relationship. And I’ll even say more – we became friends. PR included work with the government, and I worked with its left factions.

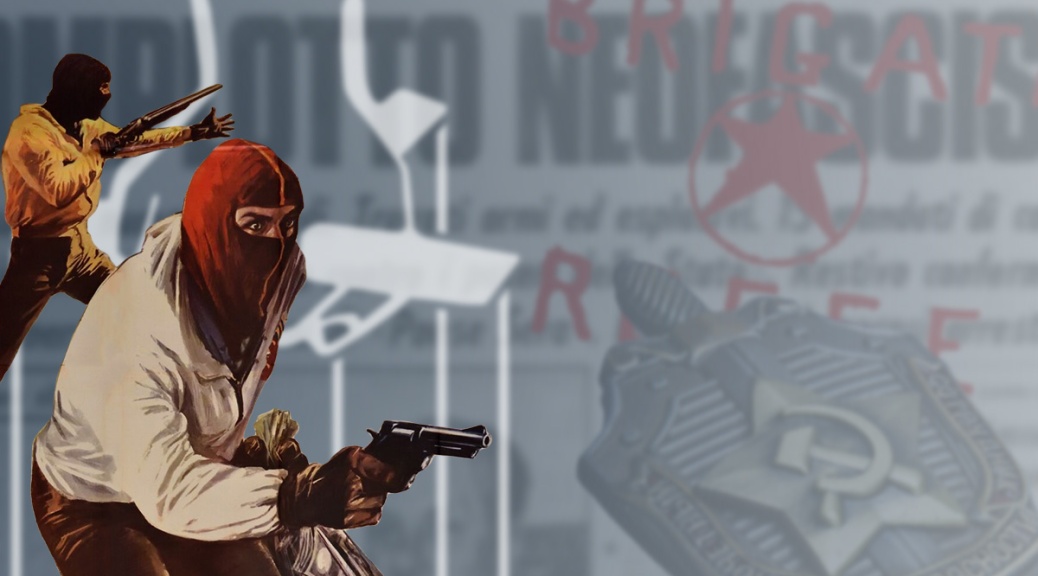

My other line of work was terrorist organizations – in those years there were the Red Brigades and neo-fascists. At that time my good acquaintance Almirante, whom I officially interviewed as a reporter for Izvestia, headed a neo-fascist party. He told me about what his party wanted, and I argued with him over his convictions about the harm and danger of communism. Moreover, we exchanged gifts – I gave him several bottles of Stolichnaya Vodka, and he gifted me several bottles of Chianti and Roscato. My line also included work on penetrating the mafia. Our intelligence service’s residency in Italy just couldn’t get access to it; this organization was closed to us. But chance helped me, and I became the first person from Soviet intelligence who was able to penetrate the mafia.

How were you able to do this, and under what pseudonym did you work while in Italy?

I’ll start by answering the first part of your question. My pseudonym was Lestkov – Leonid Sergeevich Kolosov. The two first letters from my first name, one from my patronymic and one from my last name. And I got into the Italian mafia on accident. Among my confidential contacts – not agents – was an Italian journalist, Felice Chilanti. He worked in the pro-communist newspaper Paese Sera, which was financed by the communists, or speaking more directly, by our intelligence, which transferred money from the Central Committee of the CPSU to the Italian Communist Party. This paper published our articles and printed necessary materials from the KGB FCD Disinformation Department. And as I now remember, that was led by Ivan Ivanovich Agayants.

Chilanti, about whom I was speaking above, worked at this newspaper. We met at a reception at our embassy and became friends. He often visited me at the Izvestia offices, and he also really liked our Stolichnaya Vodka, which I had in abundance. He was a very kind person, but unhappy in his personal life. At one point he was married to some countess, but she left him, and thereafter he started drinking. He somehow wrote a series of devastating articles on the mafia. Then three men showed up at his place at night, one of whom introduced himself as Nicola Gentile – friend of Al Capone, the famous Chicago gangster and drug kingpin. With Gentile were two bodyguards, and his story was such: after the war he came to Italy, where he settled. His wife had died, and his children left him.

Having shown up at Chilanti’s doorstep, he said he wanted to write a book about the mafia. But since he was illiterate, he wanted it to be written by a journalist for a very respectable fee. The book, though, was to be released under Gentile’s name. Since Chilanti at that moment was drunk, he dared to ask: “And what will happen if I refuse?” Gentile answered him: “I don’t advise you to do that.”

And so in three days’ time he was to fly with Gentile to Sicily, where Nicola would dictate the book at his villa. I requested that Chilanti take me with him. He was totally confused, not knowing how he could do that. I advised him to tell the mafiosi that a reporter for Izvestia, his friend, a journalist from the USSR, wants to write an article about the mafia. My friend asked: “But what if they shoot you there?”

I answered that it wasn’t his concern! And on the next day, he called me back and said: “Everything is fine, Lenya, they’re waiting for us. Nicola Gentile agreed to do an interview with you. We’re flying to Sicily, and we’ll be staying three days at his villa. The tickets are on him.” After this conversation I went to the resident (I was at that time his deputy) and recounted my conversation with Chilanti. He asked me if I knew what I was getting into, and what if they killed me? Then, calling me an adventurer, he proposed the following option: if they killed me, he wouldn’t know anything about my trip, but if what I conceived worked, we’d divide the spoils half-and-half.

Naturally I flew to Sicily to see Nicola Gentile. At the airport in Palermo, Chilanti and I were met by Gentile’s men, the same toughs that had visited Chilanti at night. They brought us to their boss’s villa, and it was there I first met the old man Nicola. I explained to him that in our country no one knew what the mafia was, but they all vied with each other to talk about it. I wanted to explain to the readers of my paper, just what is the mafia? To which he responded, “My son, for God’s sake! I will tell you everything, you can ask me any questions, but tomorrow. Today you and Chilanti go ride around on the yacht, catch some fish, in a word, relax.”

And on the next day began my acquaintance with Nicola Gentile. He told me a mass of interesting things. He started by explaining that many in vain consider them practically pickpockets and bandits. What is the mafia for them? In the 14th century this was a credo of struggle for Italian liberation detachments who fought the French corsairs when they landed in Sicily. And it translated thus: Morte – Death, Ai – To, Francesi – French, Invasori – Invaders, and Assassine – Murderers. That’s where the name for their organization came from. Then everything changed, and they developed their own way of life and code. Their organization adheres to the Bible, though in another version than we have. A mafioso should not covet his neighbor’s wife, and in the case of his violation of this commandment, death awaits him. The commandment “Thou shalt not steal” is observed. This means that one can steal from the state, but not from one’s neighbor. And if you steal from your neighbor, death awaits you also. One can kill a policeman, but in no case a mafioso. He showed me the mafia code. I wrote down the code and the oath for those being initiated.

According to his explanation, the mafia is a large family. Its ramified structures have information on everything; not one intelligence service in the world possesses such information. The mafia has its head, and he has three deputies who don’t know one another. And each of them has their branches that work in various areas of the economy, construction, finance and the government. I spent my time at Nicola’s villa well, and we parted ways warmly. When I would arrive in Sicily later on, he would find out about it, and the finest rooms in the city’s hotels were made available to me. Though when I was getting ready to leave, I warned him that Izvestia was a Soviet newspaper and I couldn’t write the very best about him, but I would try to write objectively. He responded, “My son, write how God puts it on your soul!” And to my question regarding whether I would be shot in Italy when my article came out, he answered that no one in the USSR knew what the mafia was, and I would be doing their advertising for them. And indeed, when I brought him the translation, he told me thank you. And that’s how I penetrated the Sicilian mafia and became familiar with its code.

What in your opinion is more important in the business of an intelligence officer: to net a source of information in the adversary’s intelligence service, or make use of the good offices of a leader of any of the parties in parliament, as to influence the formation of policy in the country through him?

No, we basically worked against their intelligence. I had an agent in Italian counterintelligence, SIFARI, who gave me information on people our service was recruiting. I would tell him the name of the recruitment candidate, and he would find out in his agency whether we were being set up to feed us disinformation. This was quite dangerous work that only two people in our residency were engaged in. And when the Italians invited me to appear on their television six years ago on “Terrorism and the Fight Against It” – to clarify whether we helped the Red Brigades – next to me was seated General Delaclesa. At that time he headed Italian intelligence and counterintelligence, called the SEFRO information service. And he told me that his service had its suspicions with regard to me since I traveled around the country, but they were baffled that I was published everyday in Izvestia. Adzhubei knew that I needed cover. But, as the general then said, I benefited them by writing about their culture and everything happening in Italy. And their analysis of my work gave the answer that I brought them more benefits than damage.

With the help of my agents, Zhiguli started its automobile production. Thanks to our work, the USSR received a credit from the car company Fiat with the construction of a factory in Toliatti. I got a rifle and skipped a rank as a reward for that operation.

I also worked with what happened within Italy’s political parties. In the left-center government in particular, I had terrific relations with Prime Minister Moro, who was shot by the Red Brigades. I received unique information from him, and he thought of me as a good journalist, not guessing that I was an intelligence officer. Within my agent network were leaders of the socialist party. But, I repeat, we were forbidden from working with the communists.

You spoke of Prime Minister Moro. He didn’t know who you really were, thinking you were a journalist. How could you get information from him?

During my interviews with him, I would ask him various complex and even clever questions, the answers to which were then analyzed. He headed the center-left movement, and this movement had a lot of enemies. In the senate the fascists, and in some degree the social democrats and Christian democrats, opposed them. Somewhere here I was managed to influence them in relation to the communist party – to find out about the tasks of the party that Moro headed, and how he viewed expanding economic ties with the USSR. After all, the deals between the USSR and the Italian companies Mattei [ENI] and Fiat were deals of the century. We gave them the gas, and they gave us the pipes. The Italians built the pipeline, despite the Battle Act, by which the US forbade Italy from selling strategic wares to the USSR. The Italians sold us them, though, thanks to my conversations with Moro. Through my agents I found out about all his inclinations, and this was extremely important for our service, which organized his visit to our Motherland.

And for the prevention of a coup d’etat in Italy in 1964, I received the Order of the Red Star.

Could you tell us about this further and answer the question as to who was giving you information about the coup preparations?

The first information that something like this was being planned I received from the mafioso Nicola Gentile during another one of my visits to him in Sicily. To strengthen the relationship with him, the Center sent me an icon for him. He collected icons. In the KGB everyone was gasping, having found out that a mafia godfather was working for Soviet intelligence without realizing it. And the Center, as I just told you, sent me an icon to consolidate the relationship with him. He asked me: “My son, are you really just a journalist working for the newspaper?” Clearly he sensed something. I answered that of course, I worked for the newspaper and wanted to write a book. Nicola said that he would be speaking with me not about a book, and he asked me to inform our ambassador of preparations for a coup d’etat with the participation of the CIA and Italy’s extreme right parties. They created such a bloc against the left center and Moro, whom they feared for this reason: he began to find a mutual understanding – not without the help of Soviet intelligence – with the communists while building up his political influence in Italy.

The coup plot went under the name Piano Solo – the Only Plan. At its head stood the military elite with General De Lorenzo. The counterintelligence chief and the military junta received approval from Segni, the president of Italy, who, by the way, was then poisoned under mysterious circumstances. But at that time he had agreed to carrying out a coup with the installation of such a regime as under Benito Mussolini – dictatorship by a military/fascist bloc. The coup was already scheduled for 4 July 1964. The plan was as follows: an officer of the air force [sic: airborne forces] would arrive for a meeting with Prime Minister Moro and shoot him. But not kill him, just wound him. And in court he would state that he did it on assignment from the communists and the ultra-left wing so that the communists could seize power. And already after that the arrests of communists would begin. There were already special camps ready for these arrests, and afterward they’d install a military dictatorship. With help from the Americans, naturally.

After this story, I asked Gentile why he told me all of this. He answered, “What are you saying, you love the Americans?” I replied to him no, and he confessed that he hated them because they had broken up his entire narcotics business both in the US and Italy. And this was his revenge. Everything I heard from Gentile I told the resident. He told me that we might get thrashed for such a message, but we nevertheless sent the encoded telegram to Moscow.

And then we ourselves saw that some kind of movement of forces to Rome had begun. We received messages from the communists that something was happening in the senate. And we prepared two articles written based on our service’s information. We sent them through our agents to the press. A most colossal scandal broke, and Moro immediately arrested de Lorenzo. And due to this scandal, the coup was aborted…

And who directed the Red Brigades, and what kind of movement was this that could grip Italy in fear with its terrorist attacks? And did the KGB FCD have any agent penetrations there?

The Red Brigades were a spawn of the Chinese, and within them I had one agent who was their main financier. The Chinese financed them namely through him. They stood for communism, but of a distorted dictatorial quality crossed with fascism. Later my agent stole a large sum of money from their treasury, and Beijing’s intelligence service got rid of him for that. After Chinese interest in the Red Brigades waned, they were approached by the CIA and the fascists. As a result, a powerful terrorist force had formed in Italy. The CIA had the mission to destroy the powerful developing left-center with their help. Some major industrialists who wanted to return to the fascist Mussolini’s times helped them with this.

How did your work against the Red Brigades go?

Work against them went through our department of active measures. Through them information about the Red Brigades would get into the press, where it would be reported what they were and whom they served. All this was done based on documents obtained by our agents. I had two agents who were active members of the Red Brigades. They worked for me for money…

Interview by Ilya Tarasov for Spetsnaz Rossii, January 2007. Included in the book:

Колосов, Л.С. Разведчик в вечном городе: Операции КГБ в Италии. Москва. «ТД Алгоритм», 2017.

Translated by Mark Hackard.