While stationed in Italy, Soviet journalist and undercover KGB officer Leonid Sergeevich Kolosov (1926-2008) was told by none other than mafia boss Nicola Gentile about the realities of power in postwar Italy. Gentile’s revelations and information provided by other agents pointed to a “secret government” running Italy through an elite masonic lodge: P-2, itself a tool of the CIA and NATO’s infamous Gladio program.

My meetings with Nicola Gentile, already without Felice Chilanti, took place on a more or less regular basis. “Grandfather” (our service assigned him this code name) took a great liking to me, especially after I gave him an antique Russian icon for his collection, so to say. At one of our meetings there was a rather strange conversation that Gentile himself started.

“Do you work only for the newspaper, my son?”

“Of course, Commendatore. I simply don’t have time for anything else.”

I didn’t even bat an eye – I’d learned to lie, boldly looking into the eyes of my interlocutor, just like they taught me back in intelligence school.

“So we assume. Although it’s very unfortunate, as I could relate much of interest, and not for the papers. You understand, my son, I very much don’t like the Americans, since they have always interfered with our business. And now they’re ever more insistently butting into Italy’s internal affairs, and into yours, by the way. Do you know why our governments change so frequently?

“Because of political instability,” I answered simplemindedly.

Nicola smiled sarcastically.

“Upon first glance, yes. Yes, that is so. Truly, where else in Europe can you find such a multicolored rainbow, as in our Italian parliament? Look at this amphitheater, where on the left sit emissaries of all possible political parties in our time, and it will become clear that not one sequence in this game of solitaire can be stable. Even the plentiful, however shrill, republicans that we call ghosts, can at any moment cause a governmental crisis, adding or withholding their microscopic weight from the political scales. And the socialists, in their swings from left to right in search of ministerial positions? Right, left, left-right, and right-left? Did it ever seem to you that this political leapfrog resembled vaudeville?”

“No. More likely a tragedy. Political instability birthed an economic mess, opened the floodgates of terrorism, and unleashed the neo-fascists.”

“That is all correct, but that’s not the point. Change of cabinets doesn’t make for political instability, but rather the juggling of this instability changes the governments. When that’s necessary for one or another reason, of course.”

“You want to say the instability is controlled? But by whom?”

Gentile’s sarcasm had reached its apex.

“By the government. Just not by the chatterers from multiparty coalitions that replace each other, but a real government, what is sometimes called a ‘shadow cabinet.’ It has been, it is, and it will be thus.”

“Forgive me, is this the mafia?”

“The mafia? No. We play these games very rarely. Have you ever heard, my son, of the masons?”

“I’ve heard, or more properly, I’ve read about them. Freemasonry, or ‘craftsmen,’ as they style themselves.”

“Well, from 1945 these ‘craftsmen’ have been ruling my country. It’s the same shadow cabinet that our all-knowing press occasionally hints at.”

I won’t conceal that at the time I was struck by the old mafiosi’s revelation. It was difficult to believe what he was saying, but also rather difficult to doubt his words. For all his political cynicism, he was a savvy man who didn’t speak lightly.

“But I’m sorry, Commendatore, what you’re saying about the shadow cabinet more resembles vaudeville than the shuffling governments.”

“Vaudeville? No, my esteemed friend. This ‘vaudeville’ will end at some point with an explosion, believe me. Do you know who’s part of the masonic lodge?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Major industrialists and financiers; influential officials from the ministries and church leaders; high-ranking military officers and directors of the intelligence services; politicians and mafia men; policemen and criminals. They’re all together but subordinated to a higher masonic leadership far away from here. Did you ever pay attention to how easily criminals perpetrate the most complex crimes in our country, and how difficult it is for our justice system to unravel the most primitive ones?”

No, at that time I took everything Nicola Gentile said as just unusual information worthy of study. Only significantly later, when a political scandal of unprecedented force thundered over the peninsula, one tied to the secret activities of the masonic lodge Panorama-2 sic [Propaganda-2], or P-2 for short – only then did I understand just how valuable “Grandfather’s” information had been…

***

Like intelligence officers, masons have always been surrounded by an aura of secrecy. However, if masons are spoken of now as if they were ghosts from long ago, intelligence officers, or more precisely their deeds – past and present – have not departed from the press headlines.

An intelligence officer, however one might feel about him, cannot work if he has no reliable agents who obtain secret information. There are enough ways to recruit agents. Here one can have a unity of views and ideological proximity; or a personal affinity; or the candidate for recruitment possesses weaknesses such as love for money, women, gambling, envy, hatred, etc… But your agent, proven in action, must become dearer to you than your own brother, for this is a value without price. Nonetheless, while he is priceless as an information source, he does have a market price since you’re paying him money. We won’t close our eyes to the current state of things – a majority of agents work for money, inasmuch as universal human values proclaimed by both Jesus Christ and Karl Marx were long ago devalued. But the real world with its market economy remains.

The old man – Nicola Gentile – showed me the secret workings of a coup being prepared in Italy and told me about the masons because he hated the Americans and Italian government for getting in the way of his narco-business. Rem, an agent I recruited, had given me most precious materials on the activities of the Italian masonic lodge “Panorama-2” sic (P-2) [Propaganda 2] and its grandmaster Licio Gelli, with whom he was close. I paid my “friend” a nice stipend, and he wasn’t a rich man. When I had exhausted Rem with requests to write an article about Italian internal politics in Izvestia, he told me very simply and frankly:

“l’ll write about what you don’t know and what threatens my country. But this isn’t for your newspaper, but for your secret service. You definitely work for them as well. You can be assured of my uprightness. I know what I’m risking. You’re hard people. But for my work I’ll need money.”

Rem didn’t disappoint. He worked carefully and honestly for many years. And now let’s shift to the masons, the Italian masons, about whom I write on the basis of one-time “top-secret” materials passed to me by my unforgettable friend…

The most promising American agent in Italy turned out to be Licio Gelli, the head of the secret P-2 Masonic Lodge. What sort of man is he? Masons don’t like to publish their biographies. But from Rem’s materials, after the scandal exposing the anti-state activity of the P-2 Lodge and its grandmaster, Gelli’s life journey appeared more or less in its entirety.

He was born in the city of Pistoia in April of 1919. He didn’t do well in his studies, for which he was expelled from school. He decided to get rich through war – he went as a mercenary to Spain, where he fought on the side of the Spanish fascists. He returned to his hometown a dedicated blackshirt. Despite his unfinished secondary education, he became the editor of the fascist weekly Ferrucio. Having sensed the coming end of fascism in Italy, he attempted to initiate ties with the partisans. His services, naturally, were rejected. And he would have been up against a wall for execution by the partisans if not for the allies. They entered Pistoia on September 8th, 1944. “The war is over, boys,” said an English officer, releasing Gelli from jail. “Don’t touch him.” And Gelli disappeared for several years and then showed up in Rome as a partner to the head of Permaflex, a firm that produced mattrasses. “Only on our matrasses will you sleep easy!” said the company’s flashy advertising. But Gelli couldn’t sleep – he was clawing towards money and power. Basically towards power, since he had already made money from the mattrass business. And then the masonic lodge P-2, splintering off from Italy’s oldest and once most powerful Grand Orient Lodge, appeared on the horizon. Licio Gelli became its member and then the grandmaster.

When on Friday, March 20th, 1981, a group of officers from the Guardia de Finanza served a thorough search warrant at the villa Vanda outside the small city of Arezzo, they weren’t looking for its owner – the head of P-2 Masonic Lodge Licio Gelli, or his friend Michele Sindona, closely connected with the mafia and accused of many financial scams both in Italy and the United States. The Finance Police didn’t discover either Sindona or Gelli. But they did find files and sealed envelopes with lists of members of the lodge, and sealed documents that set off the biggest political scandal in Italy’s postwar history.

The lists and documents were handed over to the Italian investigative agencies. I also received them from Rem. Viewing these documents, for the first time the investigators could truly conceive what type of power was behind Gelli. Here are the names that figured in one of the two lists: General Vito Miceli, Rome; Gen. Luigi Bittoni, Florence; Col. Roberto Magnello, Perugia; Niccola Picella, chief of the Secretariat of the President of the Republic, Rome; Gen. Renzo Apollonio, commander of the Tuscany Military District, Rome; Adm. Giovanni Ciccolo, Spezia; Adm. Gino Birindelli, deputy commander of NATO forces in Southern Europe, and then a deputy in parliament from the neofascist party, Rome; Luigi Samuele Dina, head of department in the Ministry of Defense, Rome; Ettore Brusco, a managing director of state television and leading editor of incoming news, etc. All of these names only became known in the spring of 1981, more specifically on June 15th, when the bombshell expose resulted in the P-2 Lodge being declared “a secret association founded contrary to the 18th Article of the Constitution of the Italian Republic…”

Italian justice, including the counterterrorist service, accumulated an overall impressive volume of information regarding Gelli’s true role in his lodge. However, right up to the beginning of 1981, the justice system didn’t take any action against the masons. Even blatant documentary evidence such as the memorandum presented in March of 1977 by Brig. Gen. Siro Rossetti, former consultant from 1971-74 to Italian intelligence chief Vito Miceli, couldn’t activate the system’s mechanisms. In his memo Rossetti (born in 1919 in Arezzo and having commanded a partisan detachment in the Resistance period), gave a detailed, meticulously verified analysis of the P-2 Lodge’s activity from 1971 to 1974. Both Gelli himself and the organization he created, along with its activities in the higher echelons of power, were subjected to scrutiny. General Rossetti was a member, without any secret intentions, of the P-2 Lodge, which he entered in June of 1970, even to participate in the work of its high council. His goal was to check from the inside just what the “brothers” of this clandestine lodge were up to, accounting that among them were leading intelligence operatives, high-ranking officers of the armed forces and police, and highly placed figures in the justice system. This is why the section of the memorandum, in which Rossetti expounds the reasons forcing him to leave the lodge and officially demand its ban, is so important.

In a way, from the second half of 1972, two P-2 Lodges were already in existence. One – the official lodge – was, as assumed, under the control of the Grand Orient’s executive junta. In the second lodge, the secret one, Gelli and his underlings enjoyed total mastery. Namely in that period, on “Licio Gelli’s personal recommendation,” intelligence service chief Vito Miceli was initiated into P-2.

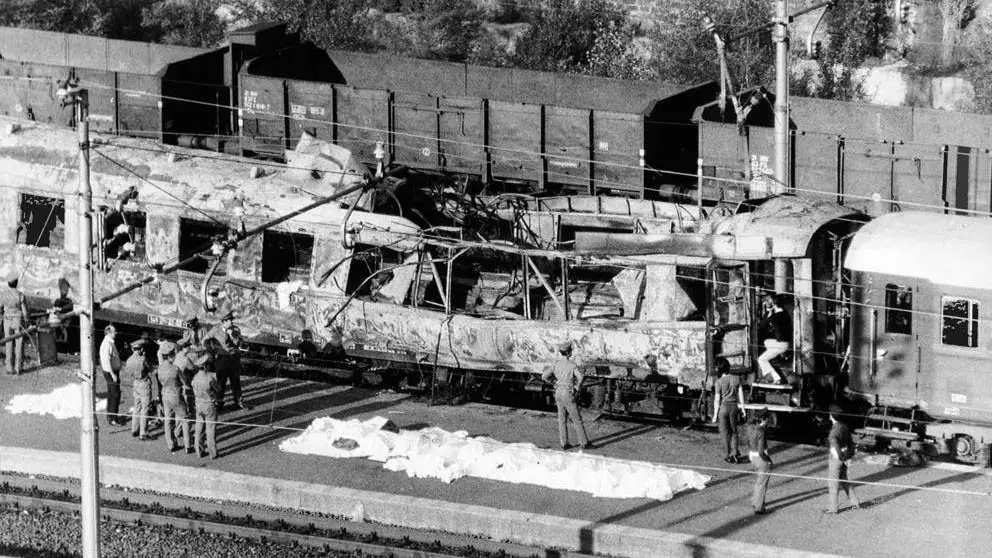

“Miceli,” recalls Rossetti, “was one of the people to whom I expressed my concern regarding the growth in influence of such a suspicious man as Gelli. However, despite my clear, unambiguously negative evaluation of this character, Miceli went on to establish close personal relations with him.” And not only Miceli. In 1974 Carabinieri Gen. Julio Grassini, future chief of civil protection. We remind that 1974 was a year of yet another coup attempt, the so-called “white putsch” designed by the former liberal Edgar Sonio and other reactionaries. It was also a year of escalation of “black terrorism” (the Brescia massacre perpetrated by neo-fascists in May, the Italicus train bombing in August) and the exposure of Wind Rose, a subversive organization of army officers. In all these conspiracies and crimes, which carried the traces of participation by foreign intelligence services and international fascist centers, the presence of P-2’s chief was uncovered without fail. Rossetti characterizes him in the following way:

“Gelli purposely didn’t conceal his vast capabilities to penetrate the most varied spheres of power and dictate his will at the most varied levels: from the secretariat of one or another minister to the presidential palace (Gelli openly said that thanks to him, Giovanni Leone was elected president), from the parliament to national and international diplomatic circles.”

Concluding his observations, Rossetti formulates the following evaluation of the masonic leadership. They are “persons interested firstly in speculating on the solidarity of masonic brotherhood they preach, to extract benefit from it for themselves.” Concerning Gelli, he adds, “the non-randomness of his relations with persons and groups, in one way or another complicit in subversive activity and invariably tied to right neo-fascist circles, is obvious. His true role in a whole string of suspicious criminal cases attests to this. All of this compels one to exclude as motives for his actions simply an inclination to intrigue, lust for riches or immeasurable ambition, but it forces us to assume connections with significantly greater centers of power of an international character. Under this point of view in particular, his claim of applying pressure to the U.S. justice system on behalf of the banker Sindona merits attention.”

In any case, emphasizes Rossetti, there can be no doubt that only “inclusion of Gelli in a certain complex mechanism of extraordinarily sweeping scope allowed the head of P-2, even with rather humble equity, to acquire an otherwise inexplicable ability to not only penetrate into any sphere and at any level, but also to apply pressure there bordering on blackmail…”

The investigation of the Italicus train bombing was approaching completion in August of 1980, when another bomb went off at the Bologna train station. And again the bloodshed of hundreds: 85 people died and 200 were wounded. The Roman judge Vella wrote at that time in a report on the activity of P-2 Lodge:

“The revealed circumstances and facts allow us to make the justified and natural conclusion that before us is an organization that, contrary to its own statutory purpose, represents the most well-supplied arsenal of effective and therefore dangerous tools of subversive political action.”

Deputy chief prosecutor of Rome Domenico Sica was given the assignment to track down P-2 Lodge’s connections with international espionage centers. During the interrogation of one of the department chiefs of Italian intelligence Col. Antonio Viezzera, accused of passing secret dossiers of politicians, trade union leaders, journalists, and industrialists to Gelli, was asked a question relating to Gelli’s espionage activity for foreign states. At this point Sica referred to articles printed earlier in the magazine Osservatore Politico, the owner of which was Mino Pecorelli, murdered by terrorists in the spring of 1979 at the entrance to his editorial office. The materials he published became a sort of last testament for the slain journalist. One of Pecorelli’s articles from 12 January, 1979, includes the heading, “The Truth About the Most Worshipful Master of P-2 Masonic Lodge.” It claimed that “Italian masonry represents an organization subordinate to the CIA.” Further Pecorelli writes: “Industrialists and financiers, politicians, generals and court officials, taking an oath of loyalty to masonry, thereby stood at the service of the U.S. CIA in order to block the communists’ path to power by any means.”

What did the journalist warn about in his last materials, written not long before his death? In one of Pecorelli’s articles, we read: “In Italy 90% of the state’s higher leadership, as well as major industrialists and bankers, belong to masonry.”

According to the materials I received from Rem, another circumstance was revealed. From 1963 a masonic lodge for NATO officers was active in Italy. Branches were created in Naples, Livorno, and Verona. Does such a lodge still exist? It’s said that it still exists and operates. Apropos, in 1969 namely that lodge attempted to launch a subversive organization under the cover of masonry to facilitate a radical turn in Italian politics. This role was allotted to P-2 Lodge, active in the milieu of entrepreneurs and financiers. In the U.S. national security sphere of the time, the figure second in influence after Henry Kissinger was Alexander Haig. During that period the future Supreme Allied Commander of NATO’s combined forces in Europe established a whole series of contacts with Italian “entrepreneurs.”

It’s worth noting that over the course of the 1970s, when the “Strategy of Tension” got its start and acquired broad sweep in Italy, Watergate broke open in the United States, and all the figures who aided in the realization of the 1969 plan left the political arena. Reagan’s rise to power, however, resurrected hopes for restoration of ties with influential U.S. actors, “friends” of the P-2 Lodge. In any case, many Italian generals and colonels enthusiastically welcomed the possibility of Alexander Haig’s appointment to an important post in the Reagan administration if he won the election. The surnames of many of these military officers were later uncovered in a long list of P-2 Lodge’s members. It should be noted that Italian masons began to show optimism with regard to Haig’s possible designation to a leading post four months before Reagan’s nomination as presidential candidate at the Republican National Convention and nine months before Haig’s appointment as U.S. Secretary of State. Also: the rushed visit to Washington of Gen. Santovito, head of Italian military intelligence and counterintelligence, literally a few days after Haig’s appointment to the post of Secretary of State, became a sensation.

Incidentally, it is known that French masons have accused P-2 Lodge of being a tool of the Trilateral Commission (an unofficial consulting body founded in 1973, the members of which include prominent representatives of monopolist circles and political figures from North America, Western Europe and Japan) and the CIA. Already in 1944, one of the documents of the OSS from 15 September 1944, No. 9a-32199, indicated that Italian right forces sought to provide terrorist groups with masonic cover in order to discredit the communist party. Strikingly, this plan coincided with the events that transpired in Italy from 1969 to 1979.

Evidently it is still too early to claim that everything in this tangled affair is known. Many moments remain unclear in a net of conspiracies that Licio Gelli wove. Gelli’s business card, by the way, is preserved in my archive. I met this man, who introduced himself as a major industrialist, at one of the receptions. And many of his acquaintances – personalities in politics and finance – continue to deny their involvement with P-2 Lodge, despite even the numbers of their membership cards having been revealed. Others admit that they were part of the secret masonic lodge but swear loyalty to the state. Some continue to stay silent. But scandalous facts have become public knowledge. And the fuller the picture is sketched out, the more obvious becomes the danger posed to democratic institutions in Italy. And perhaps they are in danger to this day.

The financial sources for the criminal activities of Gelli, somewhere on the run, are particularly unclear. But information on this is coming in. Not so long ago, it became known that he received large sums from the director of Banco Ambrosiano, Italy’s major private bank – more accurately, the former director.

…Over the Thames the fog was just lifting when a passerby discovered the body of a man hanging from a rope, the end of which was tied to Blackfriars Bridge. From his documents it followed that the deceased was the banker Roberto Calvi, who vanished without trace from Rome after the scandal of Banco Ambrosiano’s failure resulting from financial scams. Aside from the documents, twenty thousand dollars were recovered from the pocket of Calvi’s expensive gray suit. After the incident hit the print headlines, Italian journalists turned their attention to a strange coincidence. Translated from English, the name of the bridge means “bridge of the black brothers.” And the members of P-2 Lodge, to which Calvi belonged, wear black and call each other “friars.” The British police put forward a theory about the thieving banker’s suicide. In Italy practically everyone contended that “Calvi was murdered. He knew too much about P-2.”

Calvi was last seen on 29 May, 1982. At that time he was director of Banco Ambrosiano and had a mustache. Then he vanished unexpectedly.

The first to announce Calvi’s mysterious disappearance in the Palace of Justice was his attorney Gregori. No one believed the theory about his kidnapping. Some assume it was something in between a getaway and a kidnapping, or more accurately, a staged disappearance. In other words, Calvi wanted to make an escape but didn’t manage to hide where he intended. Before “savoring” the customary delights of a banker on the run, he had to resolve certain financial unpleasantries abroad. He also remained the director of Ambrosiano, and his signature was still in force. However, the justice system is interested not in assumptions, but evidence. And, overall, it was found.

Before disappearing, Calvi connected via telephone with Luigi Mennini from the Vatican Bank, a partner from Ambrosiano and financial adventures in Peru. Calvi called him to cancel an already scheduled business appointment. That’s all. Consequently the banker disappeared. Shaving his mustache so no one would recognize him, he flew on a false passport to Venice, from whence he went to the border town of Trieste and then on to Austria. There he was met by a private plane belonging to Flavio Carboni, member of P-2 and the owner of real estate in Sardinia. In the cockpit was yet another member of the lodge, Paulo Umberti. He, by all appearances, delivered Calvi to London.

On 29 May, 1982, Roberto Calvi was reading the closing statement of Rome’s general prosecutor on the case of P-2 Masonic Lodge, in which many of its members were acquitted. As Calvi read, he became ever more convinced that he had managed to extricate himself from this sordid story. At the time he couldn’t guess that in fifteen days, his corpse would hang under one of the bridges on the Thames. In a word, he now felt calm. However, that illusion didn’t last long, just 48 hours. On 31 May Calvi received an extensive letter from the Bank of Italy. By its form it was an ultimatum. The Bank of Italy’s leadership made it clear that it knew about Ambrosiano’s financial collapse abroad, especially in Latin America, where its daughter branches “undercounted” 1.4 billion dollars, and it demanded an extremely accurate explanation of how that happened. Calvi couldn’t wiggle away like he did earlier. This time the Bank of Italy intended to deal with Ambrosiano. It couldn’t, however, disclose the list of persons who had interests in the company’s foreign branches.

Thus began the finale to the madcap life of a financial fraudster, the right hand to grandmaster Licio Gelli. But Calvi was also closely connected to someone else. That was Bruno Tassan Din, director of the administrative council of the largest print publication in Italy, Corriere della Sera, a member of P-2 Lodge, and who also, like other masons, was accused of fraud. The scandal was akin to an earthquake, the epicenter of which was the most influential bank and the most influential publisher in the country. To this day many of the operators are still seized with panic. Those who played their games with money acquired from Banco Ambrosiano know that this will soon be uncovered. Those who attempted to take over Rizzoli-Corriere della Sera see how their dreams imploded. Those who hoped for a favorable conclusion to the judicial investigation of the secret activity of P-2’s chief Licio Gelli and his mason friends were mistaken.

Over the course of a long time, Calvi didn’t respond to the insistent requests from the Bank of Italy. Of course, he didn’t want to betray the secrets of his foreign branches. He resisted to the end as to conceal his dark machinations and complex financial operations, thanks to which he was able to stay afloat. He had to resort to lying. But nevertheless, the Bank of Italy still presented Calvi his bill. Practically, this was its own kind of order to destroy the entire financial system he created over the course of his ten-year period of directorship in Ambrosiano. And so that the managing director would put the brakes on everything, and without consultation from other Ambrosiano executives, the Bank of Italy required Calvi to call an administrative council, including representatives of the bank employees union, to inform them of the ultimatum. For the banker, this was tantamount to a time bomb, one practically impossible for him to disarm.

From this moment, Calvi became too much of a burdensome, inconvenient, and vulnerable character. His political patrons recognized this immediately. He still didn’t know it, but the socialists, and especially the Christian democrats, already viewed him as a “lame duck” to be expeditiously replaced. From their perspective, that was necessary to create a new, more stable line of defense for their secret interests in the bank. And in the administrative council they already found a man ready to push him off the stage – Orazio Bagnasco, a financier with a past few knew, but who had serious heft in Switzerland. Recently he had become a deputy director of Ambrosiano, with influential acquaintances among politicians.

On the afternoon of 7 June, 1982, Ambrosiano’s administrative council came together. Calvi, trying to show his respectful attitude to the Bank of Italy’s directives, read out the text of the ultimatum. However, upon conclusion he let it be known that special caution should be shown in fulfilling these requirements from on high. Bagnasco jumped up from his seat – he understood that his hour had come – and, waving the letter from the Bank of Italy, demanded from Calvi a detailed report on the situation in their foreign branches. Moreover, he wanted to study the documents that interested him at home, outside the walls of the bank. Calvi protested: “If you want to familiarize yourself with them, go into the archive, but not at home. The documents are of a secret nature, and we risk violating bank secrecy.” The issue was put to a vote. Bagnasco won by a ratio of eleven to four.

The dam had broken. It was the end for Calvi. He practically remained in solitude, having suffered defeat on all fronts.

In his time the financial scammer Sindona, with whom Calvi was closely associated, warned: “The worst thing for a financier who considers himself still influential is when the politicians – who just yesterday paid him so much attention – no longer will receive him. That is an omen of the end.” That’s exactly what happened with Calvi. When on 9 June he arrived in Rome, many doors closed before him. Only Flavio Carboni stayed around. He dealt in real estate and owned a publication in Sardinia; he had entry into political circles and knew many influential figures. For one example, he was acquainted with the deputy minister of treasury Giuseppe Pisanu. Carboni, it’s true, by that time couldn’t help, but he had his own airplane, on the fuselage of which was emblazoned the company name Aercapital.

Calvi spent the entire next day in discussions with his attorneys. In detail he elaborated to them all his unresolved problems with the judicial authorities, most of all the appellate court whose hearing was set for 21 June in Milan. But his prospects weren’t bright. Earlier he had been sentenced to four years of confinement for illegal currency export. Aside from that there were two investigations underway in Milan. One – a case of currency fraud, another – tied to a racket from 1971. In that scheme Sindona and “one executive of the Vatican Institute for Religious Works, the identity of whom was to be established.” Still further unpleasantries awaited Calvi in Rome, where five court processes were ongoing simultaneously, all of which required his attendance. The accusations were the usual – fraud, abuse of position for personal enrichment, corruption, and violation of laws on financing political parties. With bitterness Calvi would confess to his close acquaintances that he couldn’t get an audience with his former political patrons. And if any of them received him, it didn’t lead to any concrete result. “I met Andreotti the other day,” Calvi told one friend, “but couldn’t gain his support.” And so the results of his trip to Rome convinced him again: it was time to run. And he vanished.

A day before Calvi’s body was discovered in London, his personal secretary jumped from the fourth-floor window of the bank’s Milan offices. She left a note: “May Calvi be thrice cursed for the damage he caused the bank and its employees.”

Thus turned another page in the thick book of conspiracies against the Italian Republic. Naturally, it wouldn’t be the last…

Work Translated: Колосов, Леонид Сергеевич. Собкор КГБ. Записки разведчика и журналиста. Москва. Центрполиграф, 2001.

Translated by Mark Hackard.